By Bob Seidenberg

One by one, the fire companies at Evanston’s five stations took turns notifying radio dispatch they were signing out of service.

Locked in a monthslong impasse with the city, 89 Evanston firefighters walked off the job for 53 hours from 6 a.m. on Thursday, Feb. 28, 1974, until 11 a.m., Saturday, March 2, 1974, in an action that took place before collective bargaining was available for public employees in Illinois.

“Evanston firemen say they were stepped on too long,” read a headline in the Chicago Tribune.

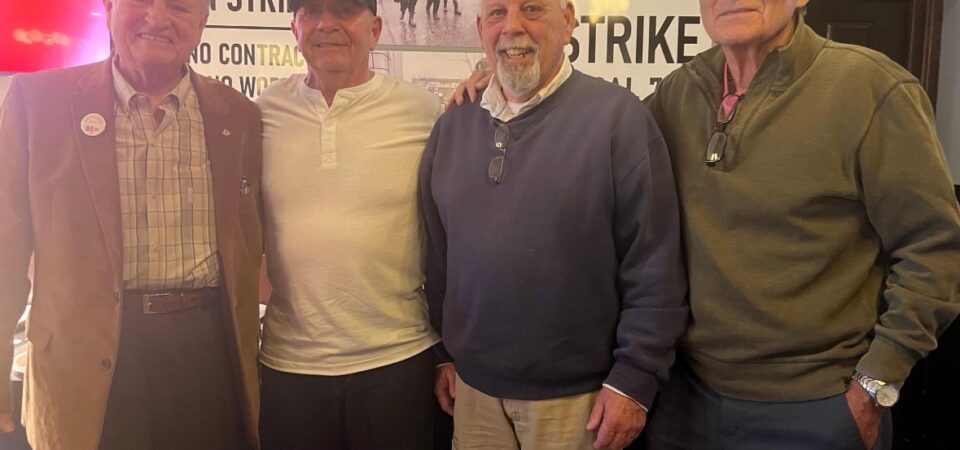

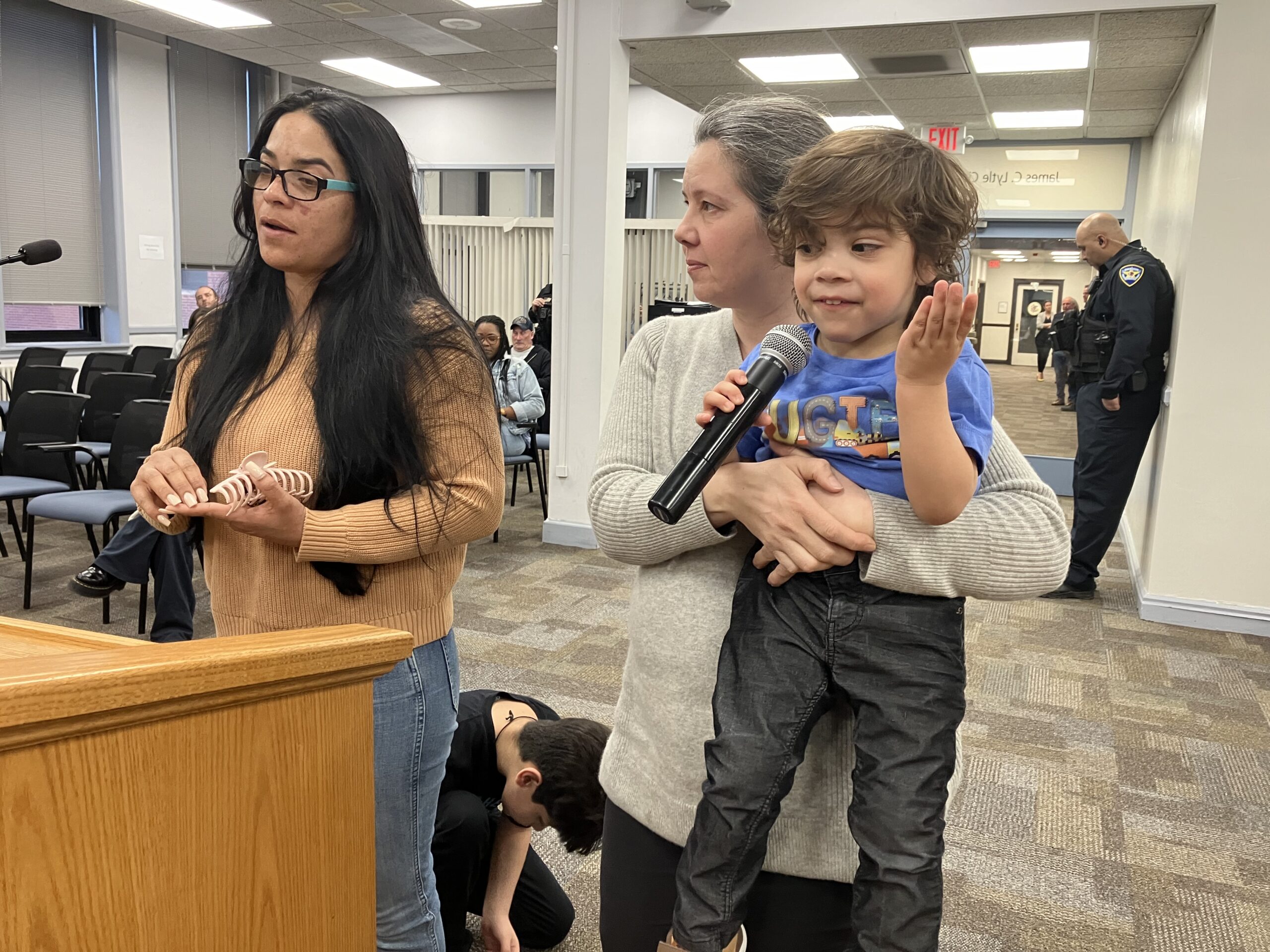

To commemorate that historic event 50 years ago, about 100 past and present members of Evanston Firefighters Local 742 and their families gathered at the Firehouse Grill on March 2.

“In many ways, the firefighters’ strike in Evanston kick-started a wave of job action amongst organized labor throughout Illinois in the 1970s,” said Billy Lynch, president of Local 742, the sponsor of the event.

“It was a bold action, for sure, but a decision that nonetheless had to be made, given the tenuous labor-management relationship that defined their era,” he said in a statement. “Firefighters put their reputation and the trust of Evanston’s citizens on the line when they walked off the job, but they were backed by strong, resilient leadership that was willing to see the fight all the way through to a positive outcome.”

‘Happy to go to jail for you’

“At that point, there were no collective bargaining rights. We had no rights,” said retired firefighter/paramedic and community activist Dave Ellis, a union leader between 1986 and 1994, who attended the March 2 event. “There was no grievance arbitration and we had no political action rights to represent the union. There was no outside consultant or somebody to help you litigate – mediators, arbitrators, whatever. And so you either came to agreement or you didn’t; and if you didn’t like it, then your only alternative was to strike – which seems you know, a little crazy for fire, police to go on strike, but that’s how it worked.”

The strike came after protracted negotiations between the union and city, with firefighters maintaining they were working longer, 56 hours a week, at lower pay, $4.33 an hour, than surrounding communities, the Tribune as well as the Evanston Review reported at the time.

The firefighters were also upset about an understaffed and under-equipped department, Evanston Review reporter Ted Bell wrote at the time.

The walkout occurred five to seven minutes before the shifts were to start, according to the various reports. Union leaders had received criminal warrants before going out, threatening them with jail sentences if they carried out the action, Lynch reported Randy Drott, one of the strikers, saying.

Preparing to walk out at the time, Drott told fellow firefighters, “I’m more than happy to go to jail for you guys,” he related at the March 2 event.

The city called in make-shift crews, including police sergeants, department heads and non-union city employees, working under the supervision of non-union fire officials to cover the city during the 53 hours firefighters weren’t on the job. There were no major incidents during that time.

On the second day, the striking firefighters shifted their pickets from city buildings to Northwestern University, in protest of the free fire protection the tax-exempt university received through the city, reported Bell.

‘These guys were beaten down’

In court on the first day of the strike, Circuit Court Judge L. Sheldon Brown, who was a 40-year resident of the city, ruled that a 1925 law prohibiting court-ordered halts to strikes in labor disputes also applied to municipal employees, including firefighters, reported the Chicago Tribune.

But a three-member Illinois Appellate Court reversed that decision the next morning, finding that the 1925 act “was not applicable to public employees acting in governmental functions and that the physical safety and protection of property is dependent on the effective functioning of the department,” reported the Tribune.

The city struck a blow for other Illinois local governments by getting the court to state that the 1925 Anti-Injunction Act is not applicable to public employees acting in governmental (as opposed to proprietary) functions, wrote Bell in an analysis piece written after firefighters returned to their job.

But the union, in winning arbitration, “did flex unused muscles,” he said, “and proved to itself that it could be more than a social club.”

In fact, firefighters, whose top-line emergency medical services is a key asset for the city, demonstrated much more than that and would go on to become a force among the city’s union groups.

Local 742 president William Curry led firefighters at the time of the strike.

“It takes a tremendous amount of leadership ability for the union to be able to be the first to go on strike in the statement in support,” said Ellis. “You know you could get fired at that point. You could get suspended. These guys all had families. The pay wasn’t great back then.”

Plus, he said, they were going against a post-World War II strong “management is always right” philosophy – there “wasn’t a collective good” operating, he maintained.

Meanwhile, “these guys [the firefighters] were beaten down,” he said. “They didn’t have masks, safety equipment. They were just exposed to whatever they had to go deal with. They lived a very short amount of time. These guys’ widows were getting $500 or $600 a month to live – I mean, that’s not enough to buy food back then, in the early ’80s. I go, ‘How can this be?’”

Key time in Illinois labor history

The action came near the start of what would be a tumultuous era in the state’s labor history.

Four years after the strike in Evanston, 24 firefighters in Normal, Illinois, spent 42 days in jail in a 56-day strike, the longest in state history.

That union was represented by attorney Dale Berry and Local 742 union representative Michael Lass, who had earlier represented Evanston firefighters.

The city of Normal, meanwhile, had brought in a Chicago law firm, now known as Seyfarth Shaw, a firm that the city would later bring in to help with its labor fights, reported WGLT.org reporters in a detailed retrospective of that strike.

A 23-day strike in Chicago followed the one in Normal. In December of 1985, Gov. Jim Thompson signed into law collective bargaining rights for police officers and firefighters. Under the new law, the Tribune reported at the time, police and firefighters “would not have the right to strike but any unresolved contract issues, including those over wage and benefits” – such as those at issue in the Evanston strike – would go to an arbitrator.

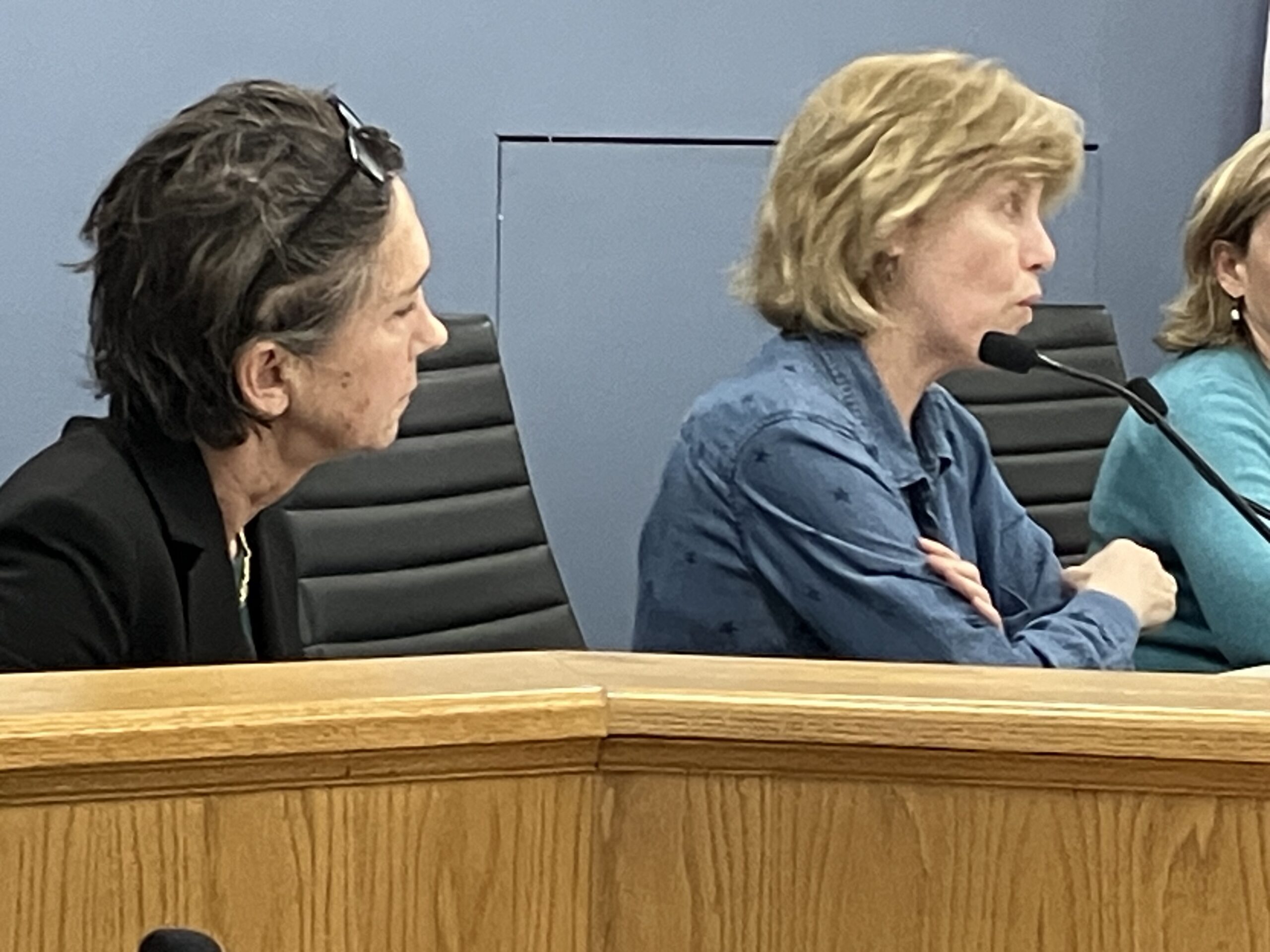

Current Evanston City Council Member Clare Kelly, who attended the March 2 event, called it “moving,” citing firefighters’ “courage and sacrifice to take this drastic measure to fight for basic workers’ rights.”

Lynch noted “that wages and hours certainly were the premier sticking points of these contract negotiations, but it was far more than that; it was equally about being recognized by the city as the exclusive bargaining agent at the negotiation table. This paved the way for firefighters’ statutory right to collectively bargain wages, hours and other conditions of employment up to and including binding arbitration.

“Five decades later, firefighters in Evanston and throughout Illinois are protected by these same statutory rights,” he said. “It’s critical we recognize this unparalleled time in the history of Local 742. We are indebted to the Evanston firefighters who walked off the job in 1974, and we should feel an obligation to pay it forward for future generations of union firefighters. Their story will not be forgotten.”