By Bob Seidenberg

As Evanston moves closer to rolling out a first-time civilian response program for lower-priority 911 calls, Rachel Williams has been serving as a roving ambassador for the new system, dropping in at different ward meetings to explain how it will work.

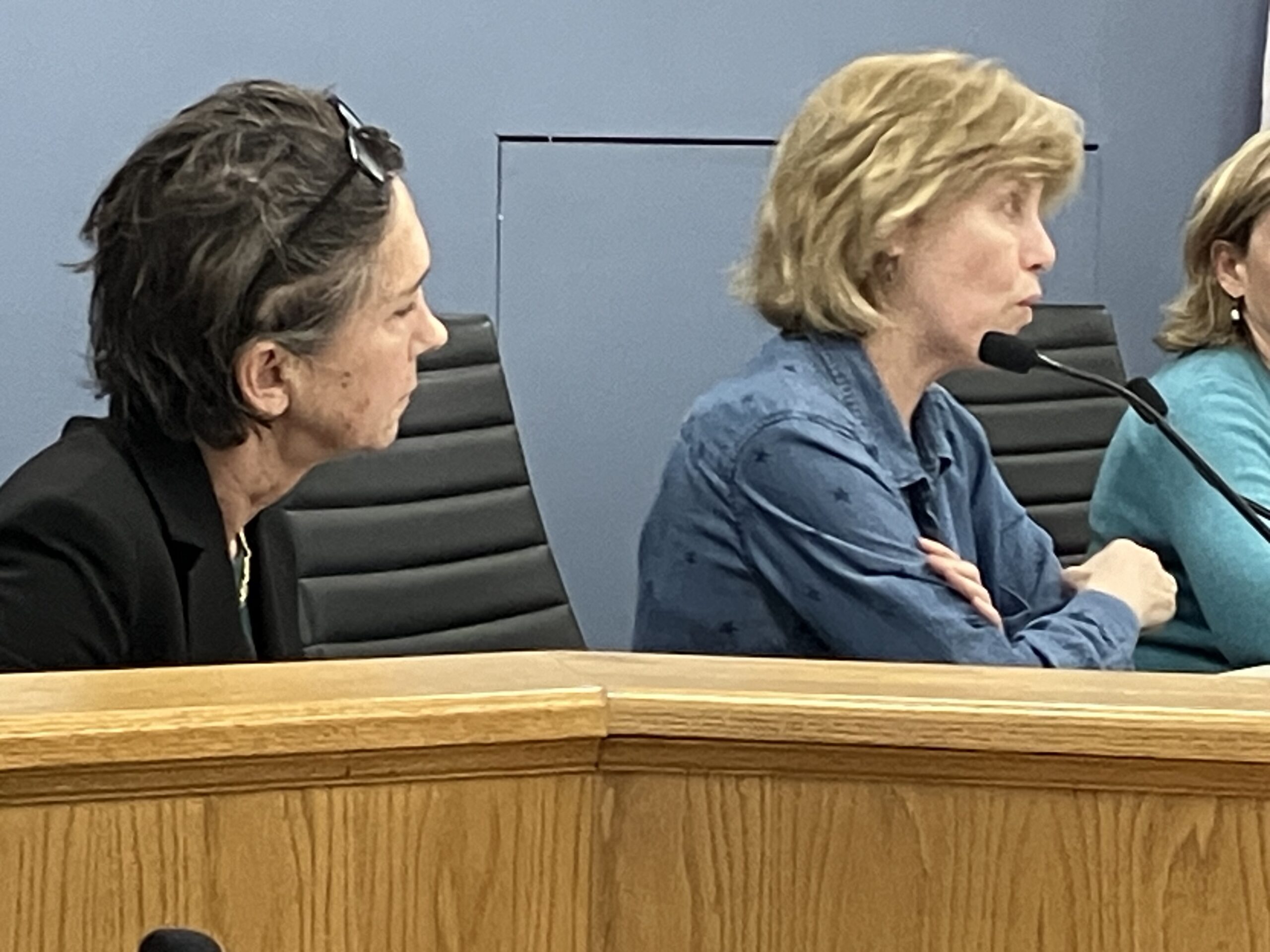

On Thursday, June 15, Williams, the city’s reimagining public safety administrator, was at the Ninth Ward community meeting at the Robert Crown Community Center. She had previously attended the Second, Fourth and Eighth ward meetings to share details and invite feedback on the proposed program.

Her appearances are all leading up to a meeting to introduce the program and receive additional feedback from the public. That gathering is scheduled for 5 to 7 p.m. Tuesday, June 27, at the Evanston Ecology Center, 2024 McCormick Blvd.

Williams said the meeting is designed as “more of a town-hall style meeting, informational about community responders and how it will be beneficial to Evanston.”

The city is working with the Law Enforcement Action Partnership (LEAP) to build a new alternative response system, using “well-trained civilian responders to answer very low-level calls of service,” Williams told residents.

“LEAP has worked with cities such as Elmhurst; Brooklyn Center, Minnesota; Milwaukee; and Dayton to explore and conceptualize what a community will look like,” Williams said.

Under the model, a new group of unarmed, non-sworn staff would respond to calls less dangerous in nature, such as wellness checks, disputes between neighbors, music and noise complaints, Williams said.

Community responders would work in teams of two, she said.

“They don’t have a 10-digit, hard-to-remember number,” she told residents. Rather, the public will be able to reach them simply by calling 911.

She said community responder teams do not generally include police. If the team has an officer on it, it is called a co-responder team, said Williams, who grew up in Evanston and returned after going to school.

Calls are divided between police and community responders. Traditionally, when someone calls 911 and it’s a medical emergency or a fire, police are dispatched to the scene, she said.

But in the community responders model, calls are triaged based on the call type, she said. If the call does not meet the community responder model, then the traditional police- or fire-response model is followed.

“We have a list of call types that were deemed eligible for community responders,” she told the nearly dozen ward residents in attendance. “These types represent calls that most likely don’t need an armed police response.”

A large list of calls may qualify

Preparing for the program to go live, the city’s community responder team has conducted a qualitative analysis of more than a thousand 911 call narratives, she said.

“As I read these narratives, the question I would like you to ask yourself is: ‘Does this require an armed police officer?’” Williams said. “If not, what type of responder would best handle the call?”

For instance:

Call narrative: Several teens, one wearing a red hoodie, gathered in an alley near a resident’s home. The homeowner “asked them what they were doing and they fled. The caller requested the alley be checked.” Categorized as a premise check, a job for community responders.

Call: “Male, unknown race, blue vest, red shirt, jeans, in front asking for money, also saying he wants to end it all.” Categorized as a well-being check.

A large list of calls may qualify

Preparing for the program to go live, the city’s community responder team has conducted a qualitative analysis of more than a thousand 911 call narratives, she said.

“As I read these narratives, the question I would like you to ask yourself is: ‘Does this require an armed police officer?’” Williams said. “If not, what type of responder would best handle the call?”

For instance:

Call narrative: Several teens, one wearing a red hoodie, gathered in an alley near a resident’s home. The homeowner “asked them what they were doing and they fled. The caller requested the alley be checked.” Categorized as a premise check, a job for community responders.

Call: “Male, unknown race, blue vest, red shirt, jeans, in front asking for money, also saying he wants to end it all.” Categorized as a well-being check.

Call: “Music coming from from a black SUV.” Categorized as a nuisance complaint.

Call: “A male and female parked inside a white van on Greenleaf are arguing.” Categorized as a disturbance.

In 2021, Williams said, some 13,000 calls qualified as community responder calls and included fireworks, miscellaneous public service, city trespassing ordinance violations, suspicious persons, drug-related activity, ungovernable youth and unsolicited solicitation.

Ninth Ward Council Member Juan Geracaris, moderating the meeting, noted that officials are still looking at different models for the program.

He said one possibility is for the program to serve as “kind of a stepping stone for someone who wants to be in law enforcement.”

One resident said there appeared to be two methods for handling the calls, one with a citation and the other with outreach for families and children. She asked how and when the city would separate those two approaches.

“That’s also part of figuring out what their authority is,” Geracaris said.

He noted that with police continuing to be understaffed, the program could offer a supplemental way to offload some of their work. He said another consideration is hours and operation, noting there are “a lot of moving parts” that officials still have to work out.

“That’s why we’re looking at all the call data to see exactly what threshold we have,” Geracaris said.

Freeing up police

Several people responded positively when asked for feedback on the proposed program.

“I don’t see a downside in this at all. I think it’s a great idea,” resident Cindy Bush said. “And I think that the people who are setting it up will figure out which model works for us.”

She said it should also free police officers to concentrate on other areas.

Fred Wittenberg, another resident, recalled during his service on the city’s environment board some 23 years ago, “it was ridiculous to call the police for gas-powered leaf blowers.”

That’s one of “many, many things,” he suggested, that the new system could address.