By Bob Seidenberg

Migdalia Bulnes currently serves as a Deputy Chief for the Chicago Police Department, and has logged 24 years of continuous service with CPD.

Offering advice to other officers, she’ll tell them when it comes to de-escalating a tense situation, the biggest tool is not their gun. Rather, it’s their voice. “If used correctly and properly you’ll be able to win situations that are extreme,” Bulnes said.

Joshua Hunt, chief of the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office Investigations Bureau, says he’s “terrified” by statistics showing law enforcement agencies across the country are losing 200 officers a year to suicide.

That number highlights the importance of mental health as officers go about performing their duties, he said. “If we don’t take care of our officers inside the walls of the Evanston Police Department, how can we expect them to appropriately take care of community service?” he asked.

Born and raised in Evanston, Schenita Stewart, Deputy Chief of Police for the East Dundee Police Department, brings 23 years of law enforcement experience, much of it in the Village of Lincolnwood. To some degree, in an administrative position, “you’re dealing with operational tasks inside, and that’s management,” she said.

On the other hand, “you need to get out of the office,” she said. “You need to be the face of the organization. You need to take advantage of every opportunity to engage the public. I don’t care if it’s the first day of school and out with other officers assisting kids going to school. I don’t care if it’s going to get lunch and making a positive contact with somebody. Every day I try to engage someone new and build a good relationship.”

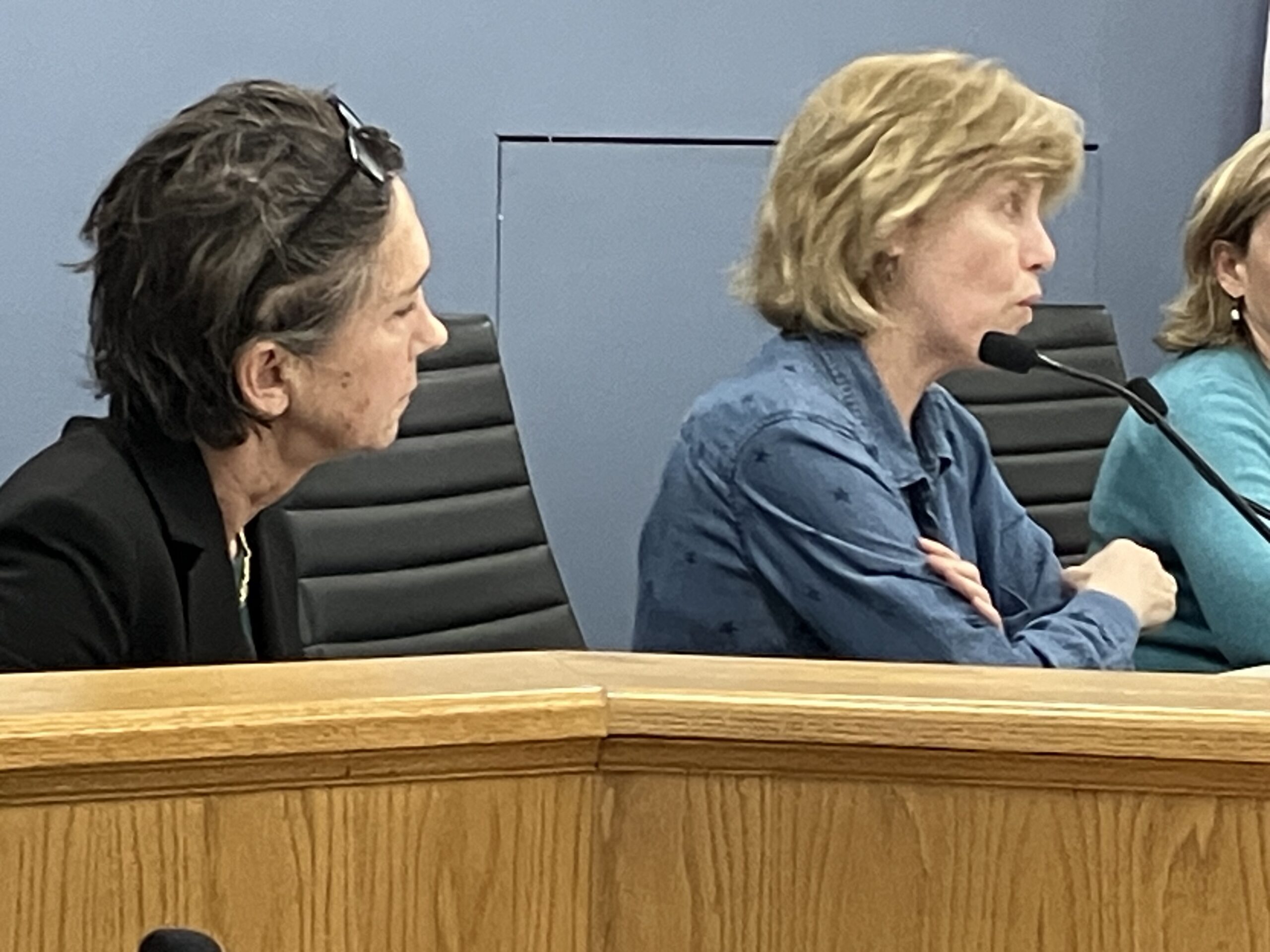

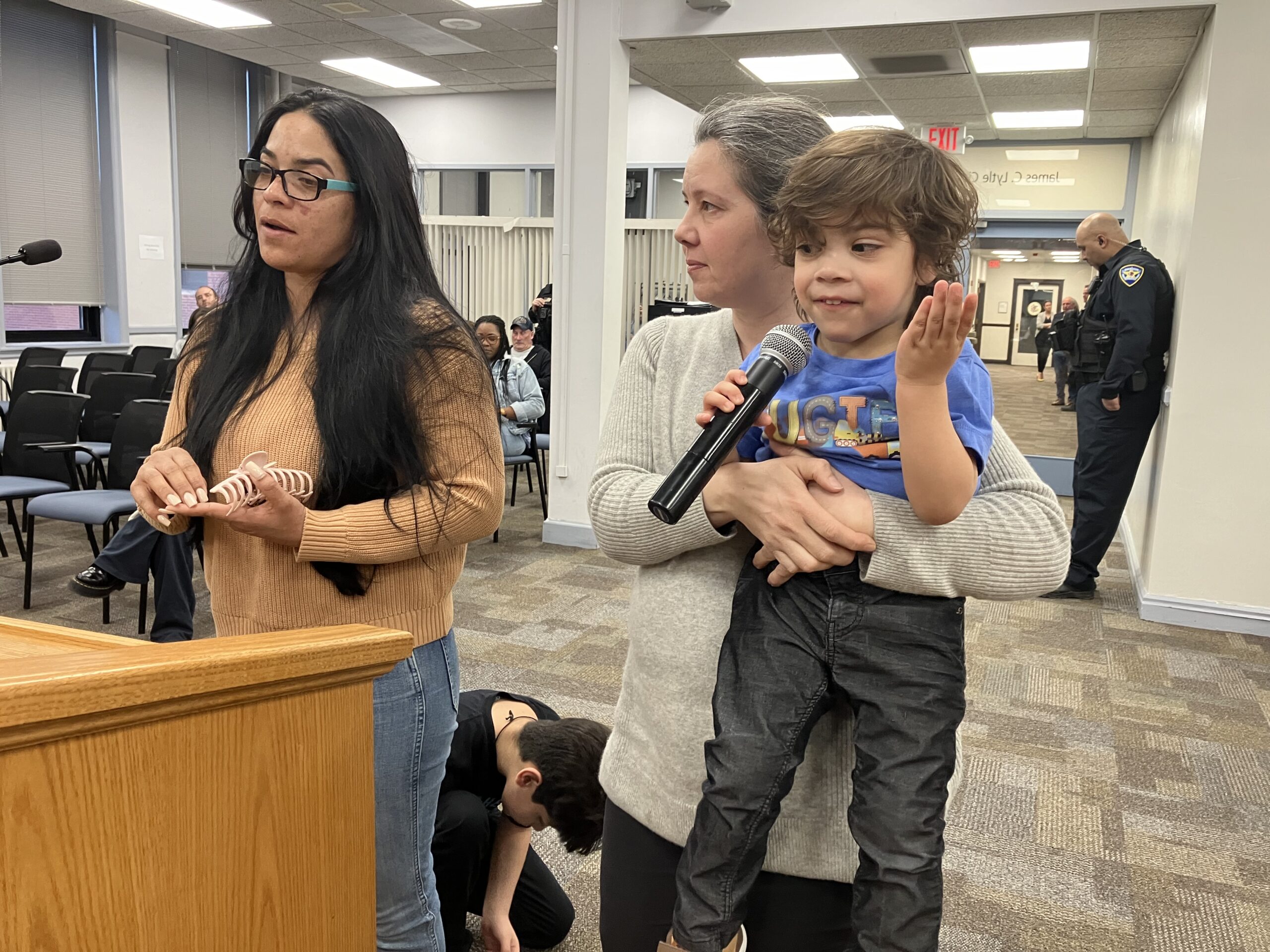

All three finalists offered their insights at a virtual forum on Sept. 8, held as part of the city’s search for its next police chief.

Sol Anderson, CEO/President of the Evanston Community Foundation, conducted the close to an hour interviews which, as much as throwing light on the backgrounds of the candidates, also brought out the changing nature of policing and the willingness of new leaders to consider methods other than force to counteract violence.

All three candidates were also asked about the Evanston Police Department’s staffing shortage and police departments’ loss of officers and what steps they would take to reverse the trend.

The interviews were conducted individually with each of the candidates at the forum. At times, more than 50 people were following online. The interviews can be viewed in full on the city’s YouTube channel. Here are some excerpted responses from the candidates.

Q: How do you feel about the urgency of bringing the department up to full staffing and what would you do to increase hiring?

Stewart: I think that’s the no. 1 issue right now, and I know it’s a problem nationally and everybody’s dealing with recruitment, hiring, retention. But I think it’s unique right now to Evanston. We need to get down to the bottom and see why people are leaving. I would like to address that by hearing from personnel – loyal people that work for this police department, that have stuck through a pandemic, civil unrest, and they’re still working here every day, and you want to surround them and give them the adequate staffing to deal with community concerns.

Hunt: I’d hate to say that this is the most important thing [the understaffing], because there’s about a dozen most important things and this one’s critical. We’re down close to two dozen officers and that is dangerous, very dangerous, to both the community and the officers. It’s dangerous in an actual rise in crime, but it’s dangerous on the mental and physical issues for the officers.

I think the first step is working with the city government to examine our pay scale and our attractiveness to lateral officers [Evanston officers who left for other departments]. Evanston lost a lot of officers to neighboring departments and I think that part of the research is reaching out to those same officers in those departments and find out what made the [other] community so much more attractive. And we have to have those conversations and really listen to what they say, and then put those answers into practical use.

And I think there’s some long-term investments and some long-term planning that I think also help offset the downturn. One is examining the viability of community service officers – unarmed representatives of the Police Department that can work to free up some of time of our sworn law enforcement officers so they can dedicate their day to proactively focusing on safety.

Bulnes: I would like to see police officers be right back at their proper staffing levels – levels where we’re able to put everybody back where they need to be: the detective division, community policing. We staff all that, so that way we have a better handle and indication when officers go into the communities. With all of that, I think staffing [through] recruitment will be my no. 1 priority coming into the department. I believe that if you staff your department and you train them, then that is the actual source you’re going to need to go out and reach the community.

The first course is to go out there and actually tap into the community’s mind. My whole motto was, in recruitment … everybody’s a recruiter, not only the police, not only my team. So having them [community members] help us is just a win for me.

Q: What would you do if you found yourself in charge of police officers with a large discrepancy in de-escalation skills?

Hunt: It is through training, but it’s also through repetition [that a department addresses the problem]. And creating a culture that believes in the philosophy. You can train people all they want, but if they don’t believe in what they’re learning, it’s going to be a harder concept to grasp. So showing the police officers in Evanston – certainly most of them already get it – that there is true value to the de-escalation, both in that exact moment and in the days and weeks that follow as you’re building positive relationships in the community. That de-escalation does work, and it absolutely works. And I think for police, for hundreds of years, haven’t done it. They’ve done the opposite. And let’s face it, it’s not working. It’s time for a change.

Stewart: Training should be a constant no matter what field it’s in. [There’s] no reason to hide from it. You’ve got to be transparent, open and honest with it. De-escalation should be part of … your policies, even to the point of safety. With the SAFETY act [the Safety, Accountability, Fairness and Equity Act passed by the Illinois legislature in 2021] as well as reform, there’s going to be constant training. We have to take advantage of this and officers need to be willing to understand that’s part of their job.

Bulnes: De-escalation is 100% our friend. If used correctly and properly you’ll be able to win situations on the street. You can take a situation that’s up here and then bring it down to right here [from high intensity to low]. I’ve been there. I know it works. So I think bringing up police officers to be trained, and to ensure it’s not a one-and-done training. This is training that goes on every year. It should be a block of training.

Right now Chicago has [it] every year. I think we’re up to … 32 hours. Officers are looking for that. They’re looking for training or looking for someone to say ‘OK, what would I do in this situation?’ And we as leaders, we have to provide it to them.

Q: What steps could be taken to address the violence that has impacted Evanston neighborhoods as of late?

Hunt: Evanston has been devastated by some really horrific gun violence in the last few weeks where children are being shot. That’s absolutely unacceptable. I do believe there are systemic issues. But we also are very serious about taking guns out of the hands of people … and [accomplishing] that’s through real, proactive work, intelligence-based policing that focuses on the targets … those who drive crime.

So that’s one [approach]. But the other one, as you’ve seen, that is making these investments and building those relationships from the police and everybody else on that [affected] block. Crime is generally perpetrated by a very small percentage. …So through effective community engagement, and building relationships with the other 99% of people on the block. If you get them on your side, you get them on the police’s side, it becomes a lot easier, and you build the trust of that community so that they assist you.

Bulnes: I think it’s important to do a lot of analysis of what’s going on in the communities. Even when I was just a commander, we had ShotSpotter [a platform that is highly data-driven] and we’re able to have pointed to an analysis of ‘OK, this is what’s going on here. This is who’s driving the violence. This person got out of jail. This is what’s going on.’ So behind that whole concept is, we know who’s driving the violence. There’s probably certain people driving the violence.

Citizens should feel safe to go to McDonald’s. Citizens should feel safe to walk in the park, or have a party in their backyard. There’s no reason that anybody has to say, ‘Well, I don’t feel safe, so I’m not going to do it.’ So taking all the data-driven analysis that we do, looking at the crime where it’s happening, and taking a look at who’s driving the violence. [Then] it’s controllable and we start reaching out to those individuals and letting them know that, ‘We know who you are. These are your options.’

Stewart: One victim is too many victims. You know, that’s where that partnership [with the community] comes in. Let’s be honest: It’s a small minority of people that are committing these crimes, that have these weapons. We have to get down to address [those] and not everybody in that ward.

You want to work with your federal programs – ATF [the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives], the FBI. We have to realize that there [are] victims, victims’ families that do deserve to be in a community that they feel safe, and that there is no violence. That’s where we want to get to, not having any violence. So not [limited] to the Second Ward or the Fifth Ward, where I grew up. I want to look at all wards and keep the city as a whole safe.

The candidates also added comments to a number of other questions during the wide-ranging interview.

The George Floyd shooting

Anderson asked Stewart in the interview about a reference she made to the George Floyd shooting. “We certainly all see videos of police shooting suspects who were running away from officers , where maybe guns aren’t involved, where there’s no threat or danger, maybe, other than a suspect escaping arrest. Do you believe that’s an appropriate response?”

Stewart:

To that point, Stewart said she had a chance to review the department’s use of force policy and, though she liked it, believes it should be tweaked.

“I didn’t see anything looking at it regarding pointing a firearm at an individual,” she said. “Why that’s important to me is that there have been some unintentional shootings and deaths of people due to having a firearm.”

As for the Floyd case, “that’s murder,” she said. “I mean, let’s be honest we call it what it is. We can’t avoid that (description) and we can’t have that happening..”

“So besides officers being charged criminally we have to have a protocol, a policy to say this is how we do it.”

Evolving with the times

Bulnes

Bulnes was asked about how she would create a police force moving into the future, that draws on what’s been good about policing while also balancing what might need to change.

Too often, “we look at police departments doing things 30 years ago,” she said.

“I think we have to look at policing as it changes and evolves with the time,” she said. “So I think looking at the police department, looking at what’s being done and restructuring the method of policing and how we conduct arrests is huge. Taking a look at that and saying ‘okay, the police can balance this out. They could do this but they no longer have to do that part.”

The ideal police officer — someone who cares

Hunt

Anderson asked Hunt to describe the characteristics of the ideal police officer.

“You can train somebody to shoot, we can train them to drive, train them to handcuff — you can train the right good reports. But you can’t train them to care,” he said. “That is the most important thing that a police officer brings to the table is that he or she gives a damn about their community. And it can’t just be I want to go catch the bad guy. It’s got to be I want to make this particular street safer for the people that live in this block. And that is the most important quality you can have a police officer. It’s not the only one. Honesty, integrity, character, heart ,all of these are important, but give me someone that cares first about making a difference over anybody else. And you can take that person and make them to the world’s best police officer.”

The forum can be viewed in full on Evanston’s YouTube channel and it also will be replayed on the city’s Channel 16.